During the “Values of Asia” study day on February 29, 2024, I had the chance to listen to Professor Lan JIANG FU, lecturer in Chinese studies at UPEC (Université Paris-Est Créteil) and doctor in History and Social Sciences of Asia. Professor Lan spoke on the theme: “The Confucian revival of management in the entrepreneurial environment in contemporary China”.

The rushang phenomenon

From the 2000s onwards,” explains Lan Jiang Fu, “China has seen a Confucian revival among the population. This revival of Confucianism is particularly popular with entrepreneurs, accompanied by a resurgence of the old term “rushang” (儒商 ), translated in English as “Confucian entrepreneur”. Historically, this term had appeared during the Ming dynasty, between the 14th and 17th centuries, and referred to a new group of merchants close to literate circles.

This revival of an ancestral term is gaining momentum, forming a social phenomenon that Professor Jiang Fu has dubbed “the rushang phenomenon”.

The rushang phenomenon takes many different forms, in a multitude of contexts. It also comes with the application in management of certain notions and references to Confucianism, and more broadly to traditional culture as a whole.

Two Confucian reads a day keep office malaise at bay

As part of her research, Professor JIANG FU conducted a field study between 2016 and early 2020 at three Chinese companies. She found that the study of classical works had become a central practice in the daily life of these companies. For example, at one company in Dongguan, Guangdong province, all members of staff, managers and workers alike, are required to read extracts from the classics twice a day, morning and evening. Both attendance and punctuality are used as criteria for assessing employee behavior. Beyond professional skills, the ability to assimilate the values promoted by the company through these readings makes it easier to gain access to positions of responsibility. Furthermore, a willingness to commit to learning the classics is a fundamental selection criterion for new recruits.

Apart from learning the classics, these “jiaohua” (教化, education) practices also rely on numerous symbolic and ritual practices designed to inculcate certain traditional values such as filial piety and humility.

Tangible impacts on management

Professor JIANG FU has identified four main impacts of the rushang phenomenon on the management of Confucian companies:

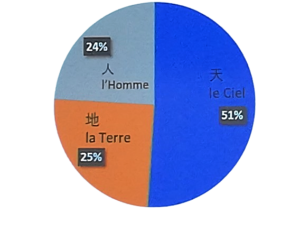

- Redistribution of profits: these companies have implemented a “51-25-24” model, in which 51% of profits are donated to public-interest causes, 25% distributed to employees in the form of bonuses, and 24% to shareholders. This approach, inspired by Confucian thought, aims to limit the profit motive beyond a certain threshold. Indeed, in Confucian thought, wealth is seen as a gift from Heaven, which must be returned to society to maintain the cosmological harmony between Heaven, Man and Earth, and thus ensure the sustainability of the company.

- Employee health protection: use of traditional Chinese medicines to care for the health of employees.

- Environmental protection.

- Philanthropy: developing charitable initiatives within the company.

A remedy for the moral crisis, in the best interests of the company

In the face of the moral crisis in contemporary China, marked by the collapse of revolutionary Maoist ideologies and the rise of materialism, recourse to the Confucian tradition, observed among both the general population and entrepreneurs, reflects a search for new spiritual resources.

And yet, this approach also has a sound economic rationale. The Confucian training provided in companies is also a means of ensuring a motivated, dedicated and disciplined workforce. On the other hand, the ethical discourse conveyed by reference to Confucianism serves entrepreneurs to build an image of virtue and justify their capitalist practices. Again, we find here a mobilization of tradition to culturally legitimize capitalism, which is far from being unique to China.

Finally, Confucian entrepreneurs’ quest for a specifically Chinese model of management and corporate culture reflects a desire to find a distinctive path to development. This approach echoes the Chinese government’s policy of building “socialism with Chinese characteristics in the new era”. Efforts to promote Confucianism and traditions are in line with this state project, and enable entrepreneurs to legitimize their activities.

More information on Professor Lan Jiang Fu’s work

A graduate of HEC Paris and CentraleSupélec, Jérôme Delacroix began his career at management and organizational consulting giant Accenture, before turning to marketing, writing and entrepreneurship.

Jérôme has been to China more than 12 times and is learning Mandarin Chinese. He hosts a YouTube channel dedicated to the Internet in China.